Types of Rating Scales in Quantitative Research

After my last post about the shoddy rating scale survey I received from an online retailer, I've received a few questions about the types of rating scales that one can use in quantitative research. So I thought it would be helpful to dive a little deeper into the two types of research scales I touched on in my last post.

If you're not familiar with rating scales, they're a common type of closed-ended survey question used to ask a respondent to assign value to something, such as an object or attribute. There are many different types of scales, but the two most common ones you'll come across are the ordinal and interval rating scales.

The Ordinal Rating Scale

An ordinal scale presents the question response options as an ordered set of categories that can be ranked, but the "distance between the categories [is] unknown.”

What does this mean? Well, we know that 3 is greater than 2, and that the distance between the numbers 3 and 2 is 1. On the other hand, we know that strongly agreeing with something is more significant than somewhat agreeing, but there is no quantifiable distance between the two categories in the latter example.

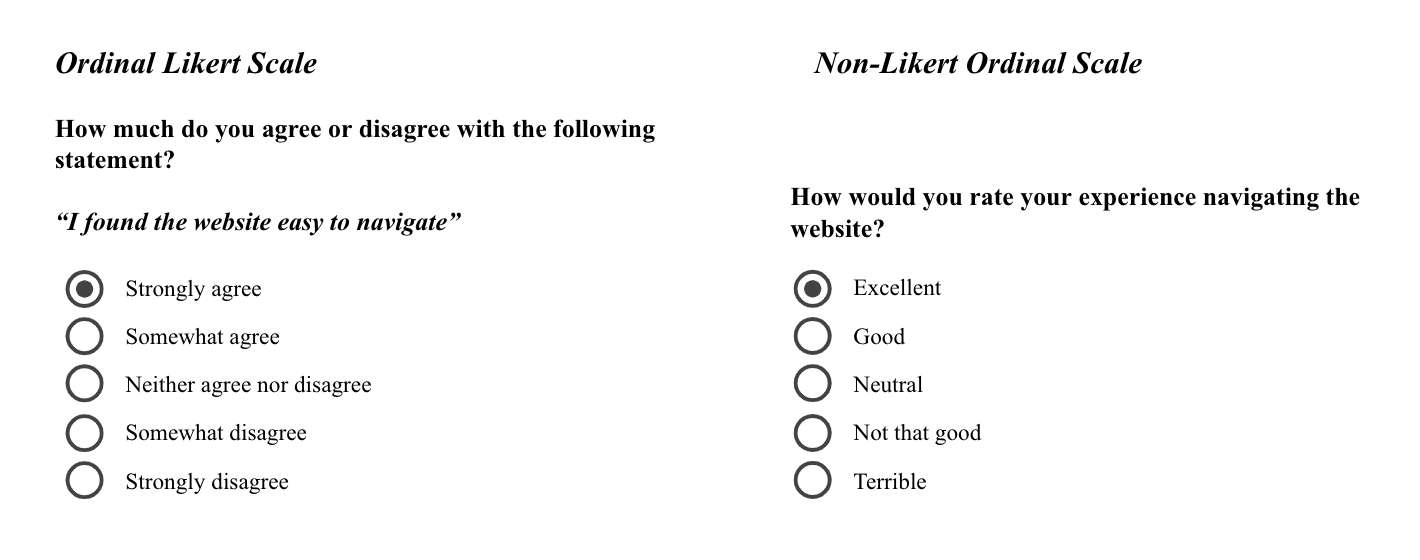

A common example of an ordinal rating scale is what's known as the Likert scale, which is named after its inventor, psychologist Rensis Likert. This type of scale is usually presented with a statement or set of statements, and the respondent is asked to rate how much they agree or disagree. In execution, ordinal/Likert questions usually look something like this.

When using an ordinal scale the focus is on the labels (e.g. strongly agree, etc) when it comes to assigning value to the object or attribute. The labels indicate the magnitude of difference between the response categories, so it's essential to use clearly distinct labels. This is why we often see adverbs like very, somewhat, strongly, slightly in ordinal scales as they help provide clear differentiation between the response categories.

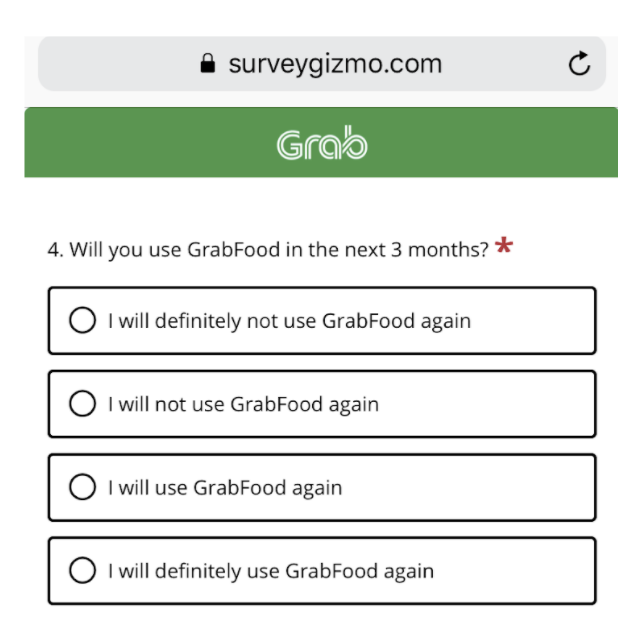

Here's an example of an ordinal scale I came across that has relatively poor differentiation between the response categories.

My problem with this scale is that the mid options (i.e. "I will not use" and "I will use") are equally assertive statements that aren't distinct enough from the options at the top and bottom of the scale. Even with the adverb definitely, saying "I will" do something is about as assertive as saying "I definitely will" do something.

What the researcher should have done here is use an adverb to differentiate the mid options. Something like this:

I definitely will not use

I might not use

I might use

I definitely will use

It's also worth taking a moment to address the design of a likert scale. As I mentioned earlier, rating scales allow the respondent to assign value to an object or attribute. But with ordinal scales such as likert, the participant is asked to rate their level of agreement with a statement about the object and/or attribute, rather than rating it directly. Here's a overview of what I mean.

Interestingly enough Likert questions are, in a way, one of the few cases where it's acceptable to use loaded questions in research, as the scale allows the respondent to disagree with the proposition.

When to use it?

Ordinal scales are my default, and I suggest using them more often than interval scales. Since ordinal scales are shorter (usually 4, 5 or 6 points) and descriptive (each interval is labelled), I find respondents have an easier time interpreting the scale and answering these types of questions.

Ordinal scales are also great for latitudinal studies where you're looking to understand a segment's attitudes and/or behaviour at a specific point in time.

The Interval Rating Scale

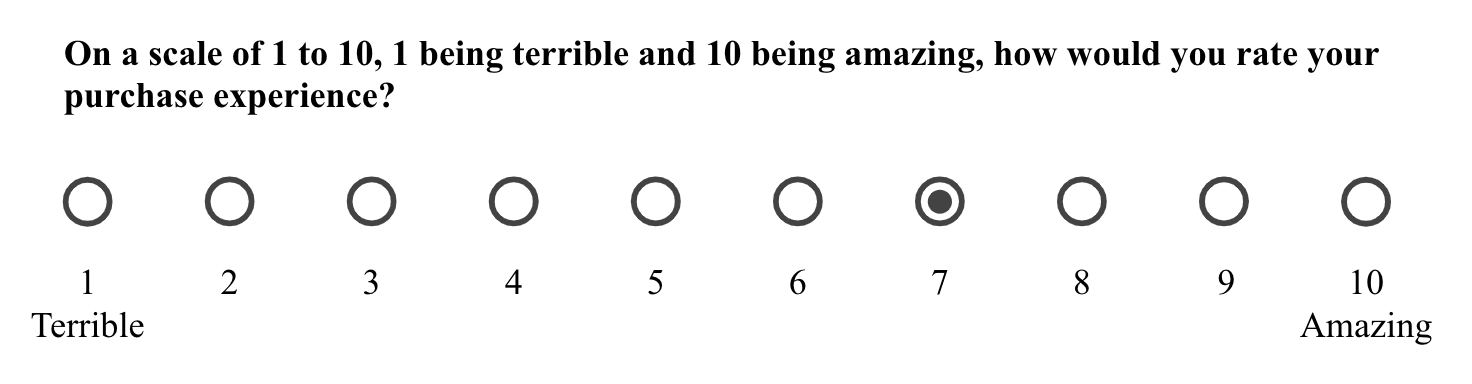

An interval scale is similar to ordinal in that the response options can be ordered and ranked. But the key difference here is that the response options are numeric, hence the distance between the intervals is quantifiable (i.e. 3 is one unit greater than 2). An important distinction with interval scales compared to ordinal is that the focus shifts from the labels to the numbers, as it's the numeric values that indicate the magnitude of difference. Interval scales also tend to utilize larger ranges, such as a 10 or 11 point scale. In execution interval scales usually look something like this:

In the example above you can see that the question text provides instructions that help the respondent qualify how to interpret the scale (i.e. 1 being terrible, 10 being amazing). Then the respondent is asked to rate the object or attribute directly. This is an important distinction, as ordinal scales, such as likert, typically ask the respondent to rate the object/attribute indirectly through a statement.

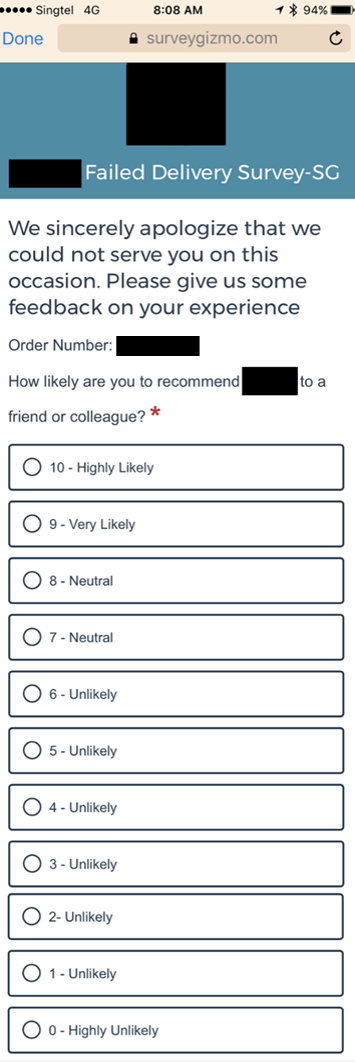

From the example above, you may have noticed that you don't need to label each interval. With interval scales, you can simply label the opposing ends and let the participant interpret everything in between. In fact, I would even say you should never label each interval on this type of scale. Doing so can distract and confuse the respondent as they'll have to interpret and assign value within the context of both the labels and the numeric values. That, and with as many as 11 points on an interval scale you'll probably have trouble finding clearly progressive and differentiated labels for every interval. Below is an example of this exact problem, which I covered in detail in my last post about research scales.

As you can see, labelling every single interval here is confusing and should be avoided.

When to use it?

Interval scales are often used to give the researcher more precision in their measurement. This is because these scales are typically longer (10 or 11 points), which gives you more data to work with. The primary benefit here is that you have more flexibility with your analysis. For example, you can analyze your results simply by calculating the mean, median or mode, or you can conduct more advanced analysis like recoding or clustering response ranges. That said, you may not always need the added precision that interval scales offer, and one drawback of these types of questions is that you can't always read the data straight away. With ordinal, it's easy enough to read the distribution across 4 or 5 points and make an interpretation. But with interval, when you have 10 or 11 points of data, your results are much more distributed, and you typically need to carry out some form of data processing first to get to an interpretation. So it’s good to be mindful of this.

Interval scales can also be better suited to latitudinal studies where you want to trend data over time. This is why we often see questions like NPS scores (an 11-point interval scale) included in brand tracking studies.

Conclusion

The ordinal and interval level rating scales are probably the most common research scales you'll encounter, but they're by no means the only types of scales you can use. Which scale you decide to apply and how will largely depend on your research objective (RO). So, never choose a scale without considering your RO, as well as the impact the scale will have on how the respondents interpret the question and what kind of data it will give you.

Looking to boost your research skills? Check out my course, Quantitative Survey-Based Research

Stephen Tracy

I'm a designer of things made with data, exploring the intersection of data analytics and storytelling